Lines of Sight, Part I: Tumelo Mtimkhulu, One final act of love

16 March – 8 April 2024

Catalogue

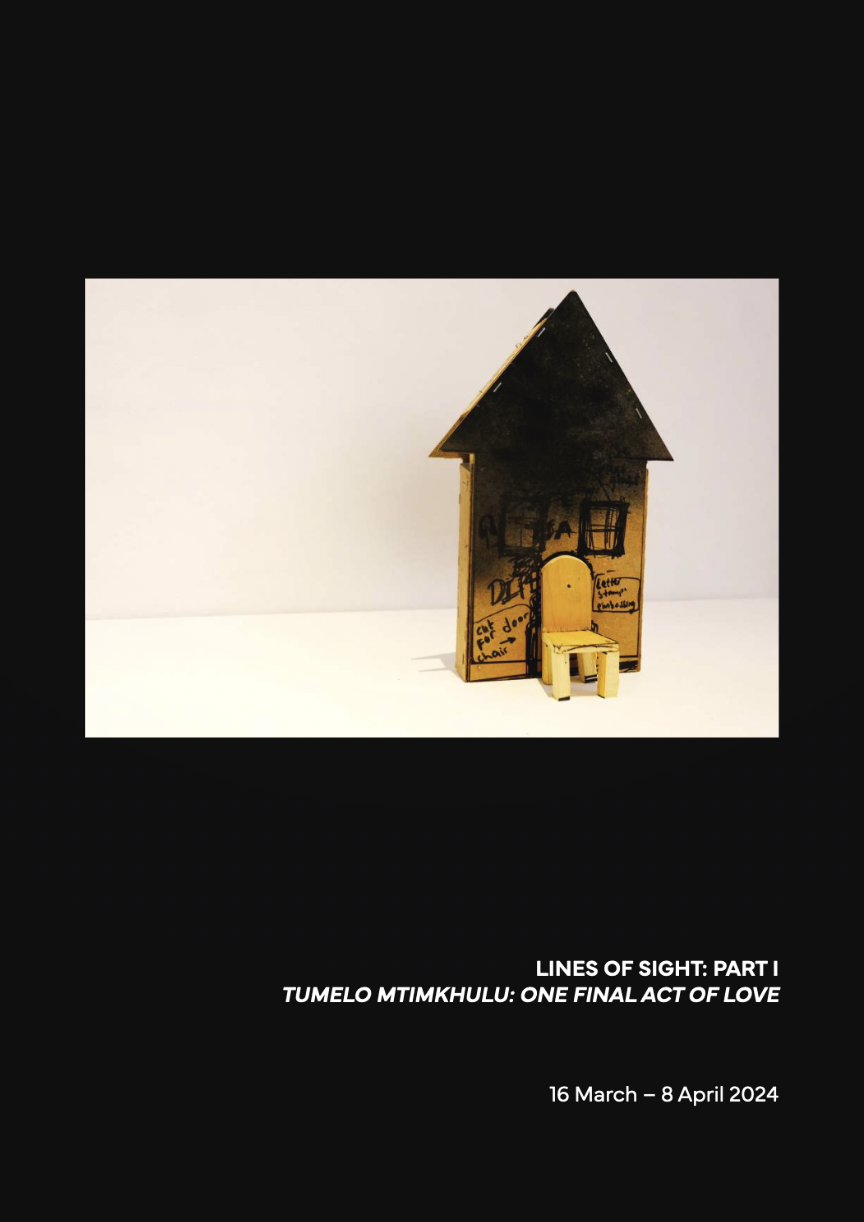

One final act of love (2023) is a sound sculpture that represents the structure of a house in its most rudimentary form — reminiscent of the houses typically drawn by children. The sound emitted from the sculpture is of the obituaries of persons who have passed on from different parts of South Africa. I have sourced the recordings of these obituaries from the South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC) radio archive; specifically from Lesedi FM, which is the Sesotho branch. The name of the radio programme is Dipihi(Dipei) tsa Bafu, which airs in the evening.

For this artwork I meditate on the memory of having grown up listening to Dipihi(Dipei) tsa Bafu; a memory that resists linguistic appropriation. Of listening to the sonorous voice of the broadcaster (often Ntate Thuso Motaung) reciting the names of the deceased, their places of birth and where they will be buried. A hymn softly plays in the background, so as to almost act as a bed onto which the heaviness of the news of death lay. Although unspoken, everyone at home sat in silence to honour the persons whom we have not known and will never know. As their names entered our home through the radio, it was as though we were being invited to grieve with each of the families. These are people who generally would not make it onto the front page of any newspaper.

The sound sculpture makes no attempt to recreate this memory but rather reifies it by ensuring that it is not a fleeting fifteen minutes, only filling the space between other radio programmes. As a sound sculpture, it gives the recordings of the names a ‘skin,’ ‘body‘ or ‘shell’ in which to exist. The sound activates the sculpture so as to enliven it. The emission of the sound from the sculpture invokes a double reading of One final act of love; in it either being a representation of the home I grew up in and the accompanying memory of listening to Dipihi(Dipei) tsa Bafu or any of the homes from which the obituaries were sent to the radio from. This reading invokes Hannah Arendt’s observation that:

Each time we talk about things that can be experienced only in privacy or intimacy, we bring them into a sphere where they will assume a kind of reality which, their intensity notwithstanding, they could never have had before.

One final act of love therefore continues from where the reciting of obituaries left off, in that the on-air reading of the obituaries is time- based and transient while the sound sculpture attempts to make concrete the grief by giving shape to it. This, when read adjacent to Arendt’s intimation that when others experience what we experience or have experienced either through the senses — the reality of our world is confirmed.

In a speculative nature, I read the sharing of these biographies by each of the persons who sent them to the radio as an attempt to give ‘shape’ to their grief. Albeit reified by the radios in each of the houses in which the obituaries were emitted, sound is an immaterial phenomenon. When read through this lens, One final act of love exists as a living monument, with the voice of the broadcaster bouncing inside the structure as a ghost would in a haunted house. One final act of love, therefore, exists as a Cenotaph. A belated reckoning dawned on me; that the physical structure of One final act of love directly links to growing up and listening to these obituaries in a home. However, another reading is that the physical structure was subconsciously inspired by my former lover who is an architect by profession.

It would be myopic to reference radio and the SABC in South Africa’s context without mentioning how it has historically been instrumental in reinforcing racial, ethnic and ‘tribal’ categories. Often termed ‘The Re-tribalisation of South Africa,’ the colonial powers employed Bantustans, Bantu Education and Radio Bantu to satisfy the colonial mission. RadioBantu’s mission was to essentially curate music and to disseminate information (or rather, mis-information) to the populace racialised as black in each of their home languages. As these radio stations still endure, it has been difficult to renegotiate their existence in in the post-apartheid landscape. In a strange way they are the embodiment of ‘ethnic’ pride while still reinforcing ‘tribal’ differences and categories that benefited the apartheid regime.